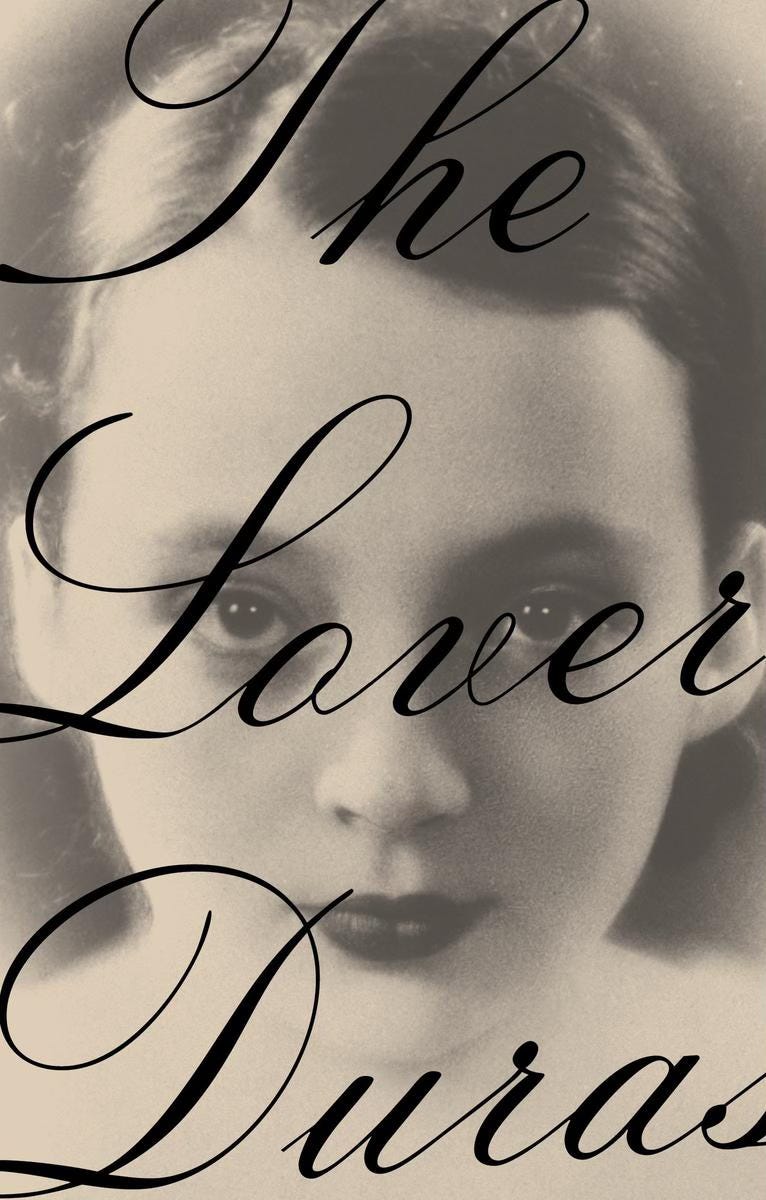

On Finishing Duras’ The Lover above the Sea

“Fifteen and a half….. I can see it’s all there...."

I finished (re)reading Marguerite Duras’ The Lover last week on a plane flying over the Adriatic and Ionian seas between Milan and Athens. Neither city has anything to do with the book. But displacement, movement, and suspended time, and presence of the sea at the novel’s end, made the experience of reading it above the sea almost visceral. Duras writes of the girl’s departure:

“For centuries, because of the ships, journeys were longer and more tragic than they are today. A voyage covered its distance in a natural span of time. People were used to those slow human speeds on both land and sea, to those delays, those waitings on the wind or fair weather, to those expectations of shipwreck, sun, and death.”

What happens in this brief autobiographical novel is well known: a 15 ½ year old white girl enters an affair with an older, 27-year-old Chinese man, the son of a local millionaire in colonized French Indochina and the city then called Saigon. For this young girl, if sensuality is as she says her pleasure, writing is the only true dream she allows herself. And for the 70-year-old writer remembering, death is always returning throughout these pages.

I listened to the audiobook while walking around Torino. In that version, Viet Thanh Nguyen offers an invaluable introduction about the “other” and the elegant, Chinese man. He provides context for the brutality of the colonizing forces that surrounded the relationship (not only during the affair but also decades later when he appears in France) and considers book’s lasting power as we lean into this voice of the young narrator determined to be a writer and the lasting power of the final scene.

One scene’s tears reminded me of Nabokov’s Lolita though Duras’ lyrical voice, the minimalistic plot, and the spiraling and circling around memories, read nothing like Nabokov’s novel. I thought of Annie Ernaux’s use of the image and photography and the longing conveyed through the spiral of past and present. I rapturously read Ernaux this past January, and like this novel, found connections all around me while I read. Some books seem to directly imprint themselves on my day to day experience. But there is less earth and time anchoring Duras’ collage-like writing, which is like her description of the sea: “formless, …simply beyond compare.”

This APS Together read (I’ve participated in many since 2020, most recently in The Odyssey) was led by Honor Moore. She gave us one word and a brief meditation each day. Below are edited versions of my notes with links to Honor Moore’s notes. Italics are quotations from the book.

So, I’m fifteen and a half.

It’s on a ferry crossing the Mekong River.

The image lasts all the way across.

Fifteen and a half. Duras repeats the phrase five times at the beginning of the book. There is both the sense of the older writer’s wonder and the young girl’s willingness to sacrifice something to experience “pleasure” and to find her own voice…we launch into the river from the port of memory, as Duras, the writer, does and we are wholly with the younger girl.

Because there is no photo of this moment, the memory of her younger self crossing the Mekong in the hat and gold shoes has more power. Because it is a memory without documentation, the image becomes refracted and gains power over time. It haunts her. The writer creates an image that isn’t, which might become, therefore, “an absolute."

Honor Moore offers a way to understand this narrative’s unstructured structure: “a torrent of themes and methods.”

“Fifteen and a half….. I can see it’s all there. All there, but nothing yet done. I can see it in the eyes, all there already in the eyes. I want to write.”

The repetition, continued, feels like an incantation, the older writer’s way to find her way into to this book, and the image she has of herself crossing the river is connected to the fact that she can see, only when looking back, that she wants to write. The girl’s impulse to write gives her the impulse to put herself in a desperate situation. She wants an extremity of sorts to write about. She already feels different. She wants a way out.

The descriptions of sexual possession are both painful and exquisite, the veering between human experience and nature itself…

Stories of sudden violence interrupt the eroticism. The 600 chicks that died in the mother’s apartment after returning to France. The chicks starved because their beaks wouldn’t close. There is something about voice even in this passage. And always something about death. Death seems tied up in with the memories of youth and loss of innocent and explorations of pleasure. Nature controls people or is forcibly controlled to a sad end.

Death is the ultimate experience of self-its loss.

Day 4: FAMILY (or SHIFT)

Family, shift, and betrayal. The intensity of the affair as it shifts into the external environment is brutal. What it must have like to write it so many years later. The cruelty of the family toward the man, the cruelty of the older brother, the cruelty of the war, and the sense of betrayal of the two suddenly named women…everyone suspicious of everyone else, untrusting and unmoored.

“My memory is of a central fear. . .I too will enter into a state much worse than death, the state of madness.”

A glimpse into this fragile narrator’s fear of the “presence/absence” of the self.

The elegant man gives the young girl a ring. The diamond ring offers a “plot twist” in this meandering, lyrical book. Classmates and teachers suddenly see the girl differently. She is a young girl who has become the embodiment of desire.

The mother sees the ring and is overcome by her own wistful memories, a diamond ring her first husband gave her, when she perhaps allowed herself desire. Then, the conversation between mother and daughter turns to: “you do know you’re unmarriageable now.” . . .the book is in some ways a love letter to the mother, albeit a tortured love letter, and in that way, it feels deeply honest.

DAY 7: THE CONVENTIONS OF ROMANCE

The elegant man shows up in France decades later to find Duras and says: I just wanted to hear your voice. In a book that is so much about voice and narration, I get the sense that this book might be, among everything else, a way for the older writer to remember and hear that young girl's voice as well.…the moment of the arrival when she is 15 1/2 on the ferry (fedora and gold shoes) is echoed by her leaving on the boat for France. The lover watches her both times.......

Earlier in the book, she says that a lover is your first way out of your family. Your way of starting to make your stories your own. The lover is this young girl’s first audience.

______

I’m not sure how many times I’ve read The Lover over the years. Images from earlier readings haunted this one, as re-readings of great books do. I’m not entirely certain, but I felt a certain flickering around the description of the girl’s first pair of high heels. In one story in my upcoming book What Mennonite Girls are Good For, a young girl acquires her first pair of high heels.

Thanks for your thoughtful, informed comments. I wrote a long paragraph outlining my own thoughts about the tale. It vanished. So, let me, instead, say that I’m still reading a used hard copy (which took weeks to arrive) with pauses to reflect on my own experiences with the subjects raised. To me, the tale is both timeless and dated, e.g., a twelve year age gap between lovers is no longer considered significant. Duras’ chunky, lyrical, non-linear writing style strengthens the whole a whole lot! Thanks again for introducing me to APS, a very good approach to moderated group reading.