On Reading Nabokov. Everywhere.

“. . .mumble, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, fantastic climax, mumble, mumble. . .”

Because I’m enroute to a conference to deliver a paper, I’ve been voraciously rereading and re-rereading him again. I’ve also been thinking about that day in the late 90s I randomly picked up a book titled Despair at a library in Somerville, Massachusetts, a book that changed the trajectory of both my reading and writing.

I remember waiting at the nearby bus stop, laughing out loud as I was pulled into that narrative voice and compulsive story, responding physically to the reading in a way I hadn’t experienced so deeply before. I remember, as if watching a girl in a movie, how I suddenly looked up to see glaring taillights through the smog of exhaust. Deeply submerged in his words, I managed to miss the enormous, roaring bus that must have pulled up, waited, and then huffed off without me.

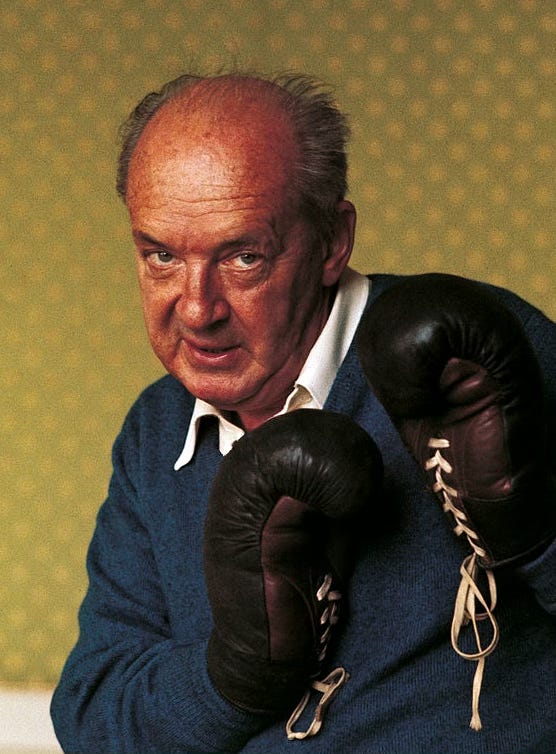

Despair is not one of Nabokov’s famous books. But after that, I jumped into the main works. Lolita and Pnin come first to mind. I read Brian Boyd’s biography The Russian Years as if it were a gripping novel. The photograph of the young Nabokov on the cover even looked to me like the Turkish man I was crushing on at the time.

A couple of years later, after I’d been accepted into an MFA program, I did a course search for Nabokov for my first fall semester and found a semester long Nabokov course offered by the Russian Studies department. I sat stupidly in front of the computer in the darkened after-hours arts department at the Globe, tears stinging my eyes.

This sentimental rush easily crosses into “poshlost,” the sort of writing kitsch Nabokov detested. He said, in an interview perhaps, that he liked books not writers. And, in truth, I don’t love all of his books. I’ve also had episodes of reading other writers’ bodies of work in a similar trancelike state and have been transformed by individual books.

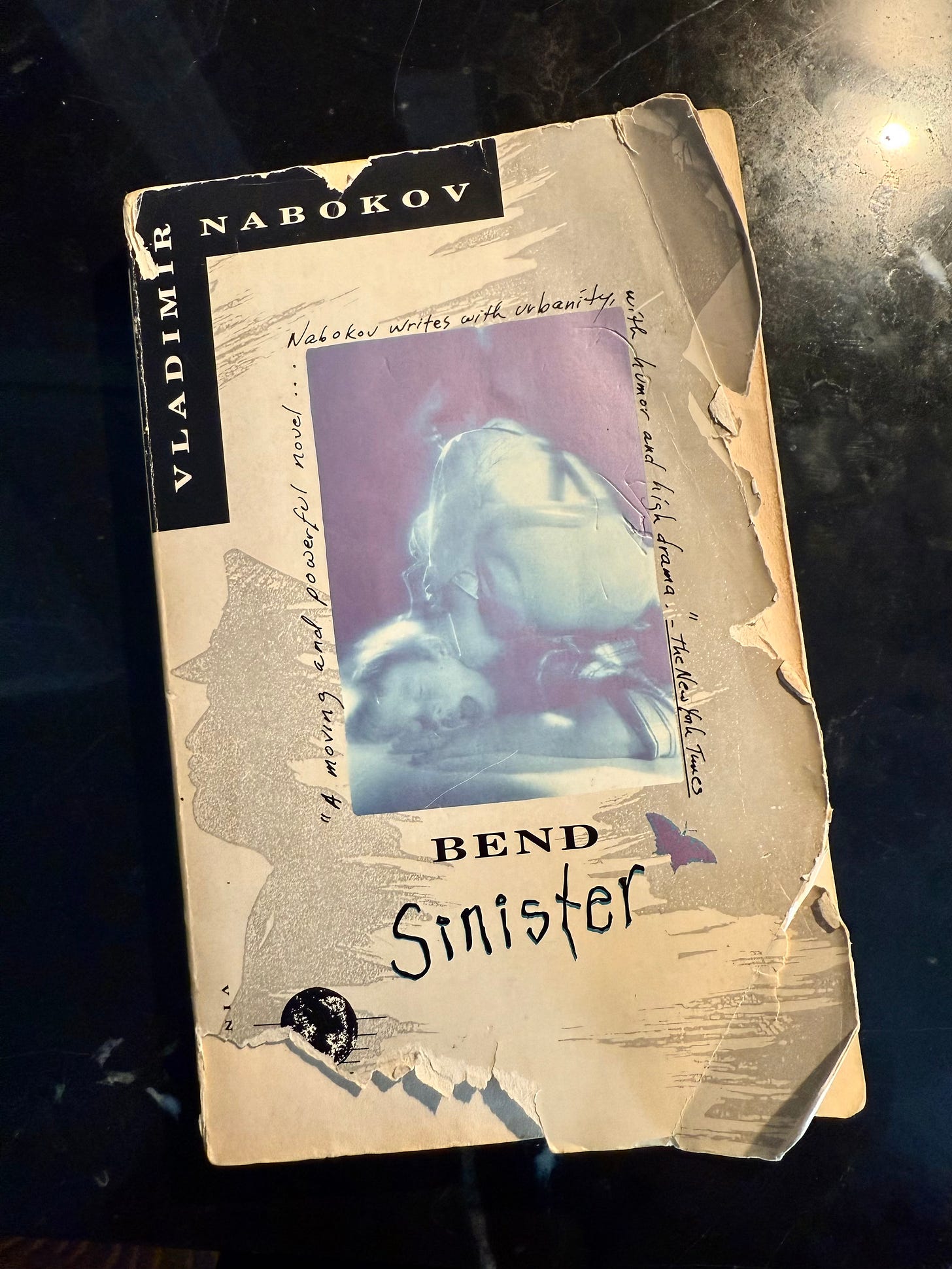

But as I’ve been re-reading Bend Sinister, “Tyrants Destroyed,” and bits of Invitation to a Beheading these past couple of months, I keep returning to the physical experience of reading Nabokov. I listen to my favorites on audiobooks just to listen his cadences. (Jeremy Irons reading Lolita, hello?) I hope to always be that girl who gets swept up by his writing enough to be oblivious to enormous busses, who feels more than knows she is on the verge of a dramatic life shift in relationship to words and ideas, not unlike Sineusov in Nabokov’s story “Ultima Thule.”

The paper I’m delivering this weekend centers on Bend Sinister, with bits of “Tyrants Destroyed” and Invitation to a Beheading. I’ve presented on Nabokov before, an admittedly odd meditation on “Ultima Thule.” But it’s the physical experience of reading Nabokov that I’m feeling after this latest Nabokov plunge. And once again, the cadence and rhythm and sound in Bend Sinister, one of his first books written in English, is part of what gives the novel and the tyrannical regime inside it such power.

In Nabokov’s Gogol, a biography, analysis, and in some sections an all-out writing manual (and a book he was working on around the time he wrote Bend Sinister), Nabokov describes how Gogol’s story “The Overcoat” works:

“So to sum up, the story goes this way: mumble, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, lyrical wave, mumble, fantastic climax, mumble, mumble, and back into the chaos from which they all had derived.”

For me, reading Nabokov often “goes that way,” too. Now, back to the chaos of getting this paper done.

That’s a seriously annotated book! 😊 Your enthusiasm reading him is reaching us here physically at our end! 😄

I've started listening to Nabokov's 'Despair'. It's brilliant!

Also, I liked your concept of a 'reading journal'. I'm likely to implement it at some point.